Akahon

Introductory Essay | Tokuho California | Akira Hattori

Introductory Essay | Tokuho California | Akira Hattori

Couldn't load pickup availability

Gunsmoke and Panels: The American Occupation and the Birth of the Cowboy in Japanese Manga

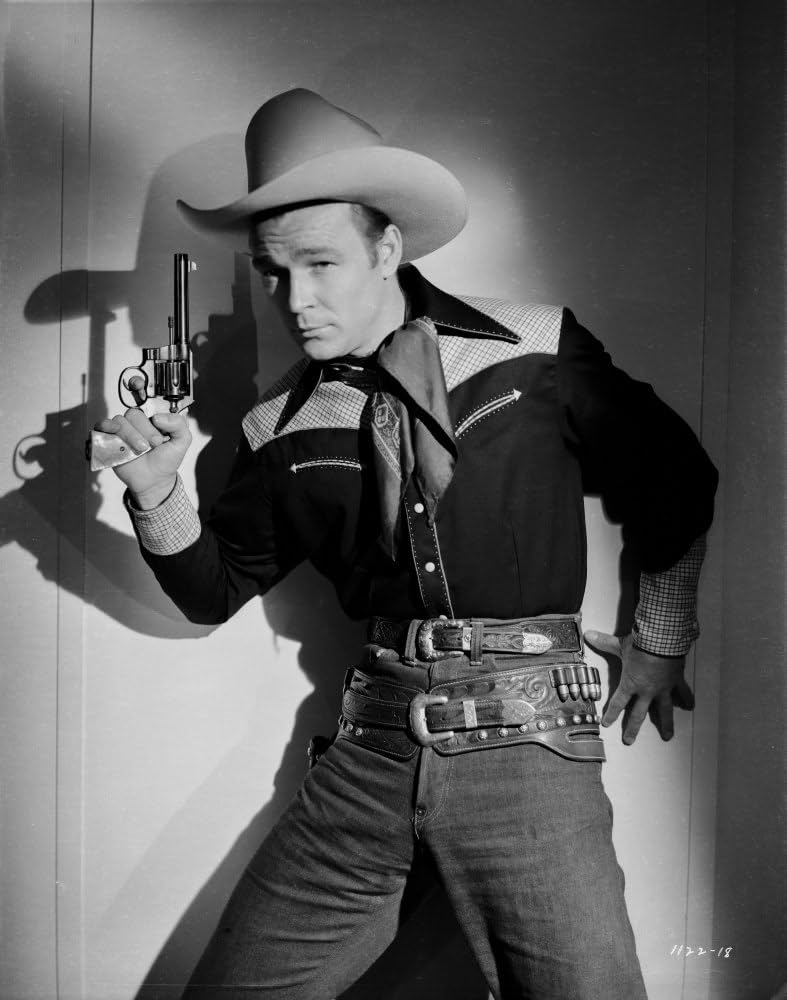

In the shadow of defeat and under the watchful eye of the U.S. occupation forces, postwar Japan experienced an unprecedented flood of American popular culture. From Mickey Mouse and Popeye to John Wayne and Superman, American icons poured into the Japanese imagination roughly between 1945 and 1952, leaving a lasting mark on its visual culture. Among the many artforms shaped by this cultural influx, manga became one of the most dynamic, absorbing and transforming American imagery into something uniquely Japanese.

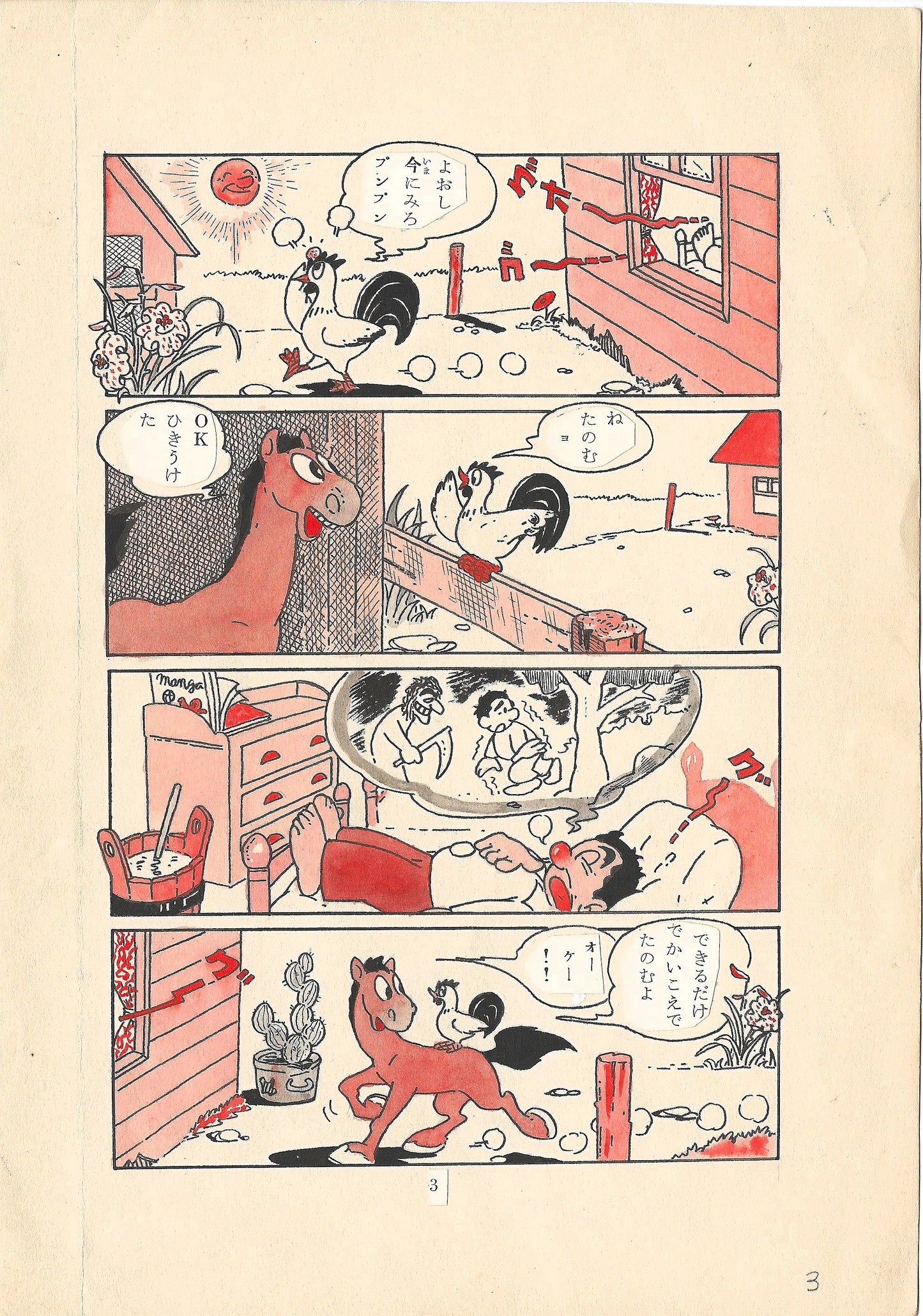

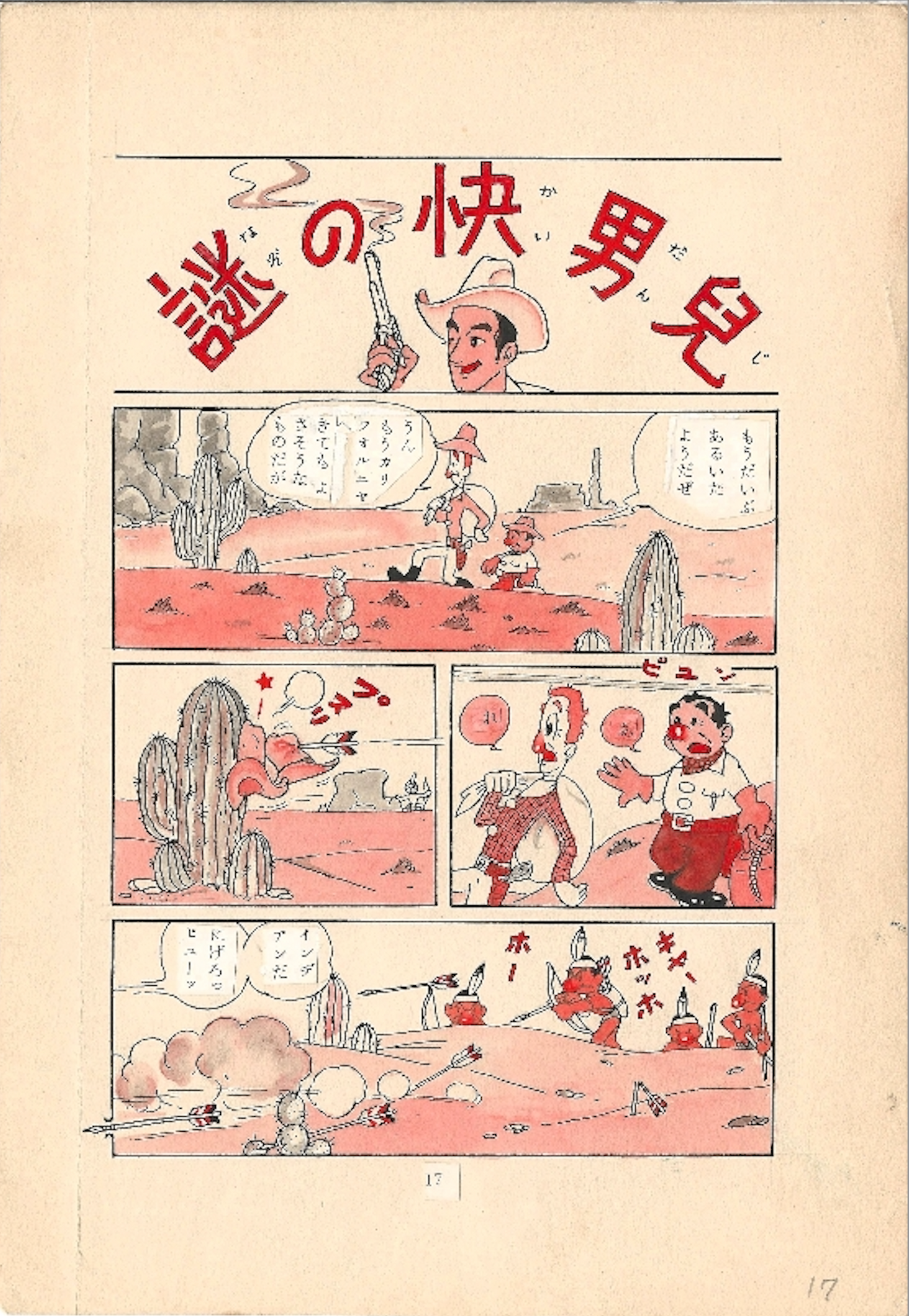

One of the earliest and most striking examples of this phenomenon is Tokuho California (c. 1949–1950), an Akahon (red book) drawn by the relatively little-known artist Akira Hattori. Pre-dating many of Osamu Tezuka’s and Shigeru Sugiura’s cowboy stories, Tokuho California stands out not only for its early date but for its bold visual style, deeply influenced by Walt Disney animation, with fluid motion, round-faced characters, and cinematic layouts. This fusion of American visual storytelling with Japanese drawing sensibilities reflects the unique cross-cultural blend that defined early postwar manga!

The story itself, rooted in cowboy Western imagery, plays out like a cross between a Hollywood slapstick and a Looney Tunes chase. Saloons, deserts, outlaws, and frontier justice are rendered with the cheerful elasticity of a cartoon dreamscape. Tokuho California shows how thoroughly the Western genre had been absorbed by Japanese artists, not merely as imitation, but as raw material for creative reinvention.

This period saw a broader wave of Western-themed manga, spurred by the circulation of American comic books and films brought in by occupying GIs. While Tezuka would popularize cinematic techniques and heroic figures in works like Angel Gunfighter (1949), and Sugiura would parody cowboy tales in his gag manga of the early 1950s, Tokuho California predates or parallels these better-known works, making it a remarkable example of early postwar experimentation. It offers clear evidence that American cultural motifs, especially the cowboy as a symbol of freedom and moral clarity, had already begun to take root in the Japanese visual lexicon before they reached mainstream recognition.

Akahon, as a medium, was particularly fertile ground for such cultural crossovers. These cheaply printed, brightly colored booklets were sold in toy stores and markets, aimed at children but often created with a high degree of artistic ambition.

Tokuho California exemplifies this duality: popular entertainment on the surface, but really, it captures a time when Japan was mixing foreign flavors into something fresh and new.

Today, the original artwork of Tokuho California is a rare surviving testament to that early mixture. As it takes its rightful place in exhibition, it reminds us that manga’s postwar development was never a single-author narrative. It was a patchwork of voices, some well-known, others like Hattori, unjustly overlooked, who together forged a new visual language from the wreckage of war and the glow of imported dreams.

Share