Masao Tanaka

Biography | Masao Tanaka

Biography | Masao Tanaka

Couldn't load pickup availability

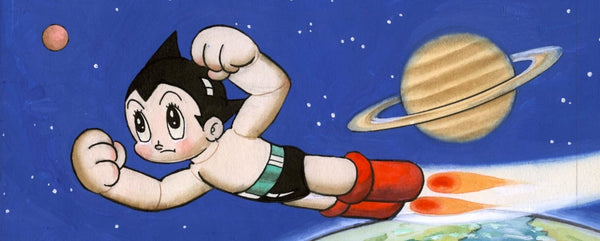

Masao Tanaka (田中正雄, 1927–2014) was a Japanese mangaka active from the late 1940s through the 1970s. Born in Osaka, he belonged to the postwar generation that helped shape early shōnen and, to some extent, educational manga.

Tanaka’s first publications appeared in the late 1940s, with regular contributions to newspapers and magazines. His early akahon work includes The Underground Kingdom: The Mysterious Land Beneath the Earth (Tōkōsha, 1951, under the name Umehara Hajime), a story steeped in postwar sci-fi fascination, subterranean civilizations, artificial life, and speculative adventure very much in the spirit of Tezuka’s Lost World and Metropolis.

Soon after, Tanaka lived and worked for an extended period in Tokiwa-sō, the now-legendary apartment building in Toshima, Tokyo, famous for housing many rising manga artists. Tokiwa-sō functioned as a genuine creative incubator, where collaboration and artistic exchange thrived.

Tanaka lived in the same modest conditions as his neighbor Osamu Tezuka, a simple six-tatami room in a creaky building, furnished with little more than a desk and a bookshelf.

The surrounding neighborhood was home not only to Tanaka and Tezuka, but also to creators such as Shimada Keizo, Takano Yositsu, Haga Masao, and Yamane Hifumi. The location had originally been found for Tezuka by the publisher of Manga Shōnen, and since Tanaka was working for the same magazine during that period, it is likely that the publisher helped him secure a room there as well. This small cluster of apartments effectively became a manga production hub, where proximity made it easier for editors to collect manuscripts and for artists to exchange ideas. Tanaka thus found himself within one of the earliest artistic centers of postwar manga.

As the 1950s progressed, Tanaka continued to publish steadily. Works such as Santaro the Spear, Cheerful Ken-chan, and Who Is the Culprit? demonstrated his clear storytelling and inventive imagination. He explored science fiction, humor, adventure, and historical subjects, but for many years he did not yet produce a long-running series. His style remained firmly shōnen: accessible artwork, brisk pacing, and a keen sense of what could engage young readers. His shōnen storytelling also introduced young readers to Japanese history in an engaging, accessible form, and his historical manga opened a path to the mangaïsation of literary classics such as Robinson Crusoe.

Tanaka began diversifying his work and responsibilities, devoting time outside his manga activities to the traditional sword art of iaidō. He trained to become an instructor, a role that required continuous practice and teaching. Balancing these commitments affected the rhythm of his manga output for a time. After a four-year hiatus, he returned with Nice-kun, which at first glance appears to be a typical baseball-themed shōnen story… until you begin reading it.

Tanaka’s dedication to art and teaching extended into his personal life. His daughter, Keiko Tanaka, carries forward his artistic and martial sensibility. His studio, preserved as Masao’s Atelier, offers a view into his long working life, complete with his original table, chair, and drawing tools.

Masao Tanaka stands as an important figure of the postwar manga generation, shaped in part by the creative community that formed around Tokiwa-sō.

Share