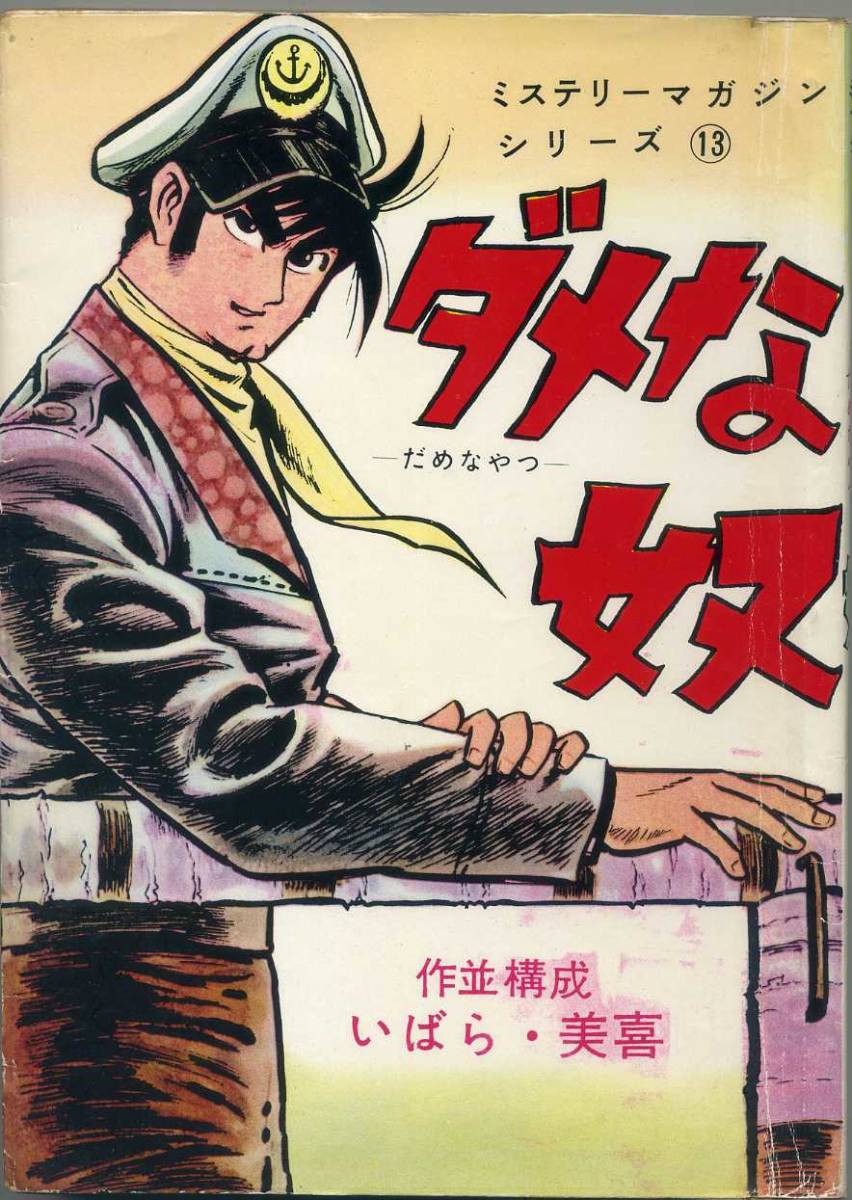

Miki Ibara

Biography | Miki Ibara a.k.a. Miki Thorn

Biography | Miki Ibara a.k.a. Miki Thorn

Couldn't load pickup availability

Miki Ibara (いばら美喜) a.k.a. Miki Thorn (1928-1983)

Real Name: Noboru Fujisaku (藤咲 昇)

Miki Ibara was a Japanese mangaka active from the 1950s through the 1970s, known for his work in the rental-manga (kashihon) industry, a parallel publishing circuit that allowed artists to explore darker, more adult-oriented themes.

After completing secondary school in Mito, he briefly studied at Musashino Art University but left for financial reasons. In the 1950s, he supported himself by drawing street portraits in Tokyo before turning to manga.

Ibara’s work is firmly associated with the gekiga movement , which sought to give manga a more adult, realistic, and cinematic tone. He collaborated with publishers such as Hibari Shobō (ひばり書房) and Rippū Shobō (立風書房), specializing in horror and dramatic stories.

In 1962, he joined Saitō Production (さいとう・プロダクション), founded by Takao Saitō (1936–2021), where he worked alongside artists such as Shinji Nagashima (1937–2005).

His stories are notable for their dark atmosphere, graphic violence, and exploration of social and familial fatality, blending psychological drama with horror visuals. Some of his best-known titles include:

- 刀の錆 (Rust of the Sword, 1964)

- 怪談!!黒猫 (Ghost Story!! Black Cat)

- 化け猫少女 (Bakeneko Shōjo / Demon Cat Girl)

- 恐怖の修学旅行 (The School Trip of Fear)

- 悪魔の招待状 (Invitation from the Devil)

Among his most remarkable works is 面よごし (Faceless Eyes, 1966, Tokyo Top Company) in the 'Bad Guy' series inspired by Georges Franju’s French film Les Yeux Sans Visage and Gothic Hammer adaptations, the story depicts an aristocratic family afflicted by a genetic disease that disfigures its members.

To maintain a human appearance, they remove the skin of their victims’ faces to use as masks. Faceless Eyes demonstrates how Ibara adapted Western horror cinema into the Japanese gekiga style, combining striking visual storytelling with a carefully developed narrative.

Although Ibara was not a founding member of the gekiga movement, his rental-era horror and dramatic works are considered part of the same historical and stylistic milieu that gave rise to gekiga, bridging the postwar rental-manga scene with the mature storytelling that defined the genre. He also appears indirectly in Shigeru Mizuki’s autobiography, reflecting his presence in the small, interconnected world of postwar manga artists.

Miki Ibara remains an important figure in the history of adult-oriented manga and early gekiga, notable for merging horror, jidaigeki, and psychological drama into visually and narratively sophisticated stories.

Share